Artist Cory Basil Finds New Inspirations in Lockdown

Once the pandemic is over, what will we have to show for our time at home? Will we be better off? Or will those of us who stayed at home regret not making the most of what felt like a prolonged snow day?

As time is a precious resource, Cory Basil doesn’t want to waste a single moment. The filmmaker, sculptor, painter, illustrator, musician, and writer doesn’t just march to the beat of his own drum; he conducts a symphony of ideas and creative impulses, following the score as it unfolds inside his mind. The proprietor of “Imaginebox Emporium,” one of the most popular stops of the Franklin Art Scene’s Art Crawl, is incessantly creating and experimenting. Still, he has a tough time boiling down what he does, and Cory tells Launch Engine that defining him would depend on what project he’s working on at the moment. He says, “A label could be ‘artist.’ I’m happiest and most comfortable when I’m in my own element creating things. Whatever it may be—music, writing, painting.”

“I’ve always drawn,” he says. “I was just one of those kids; as soon as I could hold something in my hand and make marks, I did.”

Cory’s compulsion to create art started with the childhood dream of being an animator for Disney. He was fascinated with the 2-D, hand-painted, and hand-drawn animations and the visual effects created by maestro Ray Harryhausen’s clay animation films as well. That dream changed, however, after he experienced his first concert at age 15. After that, he wanted to try making music.

He earned some success as a musician. Starting his first band at the age of 15 in the garage of his home, he’d go on to spend the better part of the next 20 years building an extensive catalogue of songs, touring around the country and other parts of the world, as well as learning the music business inside and out.

But the impersonal nature of the music industry siphoned the fun out of creating for Cory, which he perceives as an almost-sacred act. Cory stepped away from the business of being a recording artist. He says, “After the initial pain that comes with letting go of a lifelong dream, it was refreshing to put it on the back burner. Only tapping in on occasion for my own enjoyment and satisfaction.”

Sensing that his abilities could be used elsewhere, he focused on web design and animation to pay the bills, adding gig work to round out his earnings. Cory acquired his first freelance artist assignment when he was 12 years old, and he’d continued earning money in his adolescence decorating restaurant windows for the holidays and designing flyers for businesses. After much life had passed, a friend recommended that he have a solo art show at a local coffee shop, Cory reluctantly agreed to his first public exhibition. It was an event that drew in over 60 attendees, with half the exhibited art selling on opening night.

Cory didn’t have a mentor offering to help him learn a creative field. And perhaps he didn’t need one. That first show gave Cory the confidence he needed to keep making art.

Another watershed moment was Cory’s visit to the New York City Museum of Modern Art’s 2009-2010 Tim Burton exhibit. That show let him know he wasn’t alone in his perspective on the world. “That was the first time my own world began to come together. I was able to connect the dots,” he says. “Here was somebody else who had gone down this disjointed path, creating all sorts of things that didn’t make any sense. From sculptures to primitive animations, wild sketches, and off-the-wall characters; to writing little humorous stories, poems, and filming bizarre home movies. Going to this retrospective of Burton’s life really lit a fire in me and made me feel like I wasn’t as much of a lone ranger having no path or direction. Someone else had a beginning like this and was successful.”

Sharing that it’s always felt like he “was all thumbs,” Cory accepted that creators might forever feel a little uncomfortable, as each new piece is an experiment that will take an artist just past their point of familiarity. He says that the decision to stick it out “definitely made him a better artist.” He says, “Every artist has to start somewhere. And so, you kind of glean from what your taste tells you is good art. You spend thousands of hours practicing, smoothing the edges. If you do it right, and you’re true to yourself, you leave all of what inspired you initially behind. And after much failure, much rising from the ashes, your ‘true self’ emerges in your work. The greatest myth of the arts is that one is born with the ability to make magic. Every bit of it is fought for and earned.”

That ‘true self’ that Cory sees manifested is one that is whimsical, hopeful despite its surroundings, and animated by a matured spark of a child’s imagination—one that was never extinguished by the bitterness or ennui rife in adulthood. The extremes, the heightened elements of light and dark, in his work serve as a beacon summoning those same thoughts that others might have but struggle to express. Cory shares that he never intends for an art piece to be merely furniture or just hung on a wall for its looks alone. Cory says, “Everything I do is pulled directly from my heart and soul… Each individual piece speaks from a place within me. My hope is—in remaining true to this philosophy—that the pieces of myself stitched into a work of art find the viewer and speak to a place they’ve neglected, or a place they didn’t know existed.” It may seem like a peculiar reward, but Cory has observed multiple patrons of his art “who are leading lives trying to avoid emotion” become uncomfortable viewing his artwork, as “it’s made them feel, it’s made them connect.” Cory explains that while it may initially be uncomfortable for the viewer if they remain with those feelings, there’s a chance for growth and true discovery. He says, “That’s exactly what I want… that’s what I believe my purpose is.”

The excavation of those feelings—the ones not totally dealt with—is how Cory pays his bills. Just like someone working in a mineshaft, Cory’s daily grind as a professional artist and writer means finding an idea, looking at the creative options to bring it to life, willing the idea to manifest, and racing against the clock or self-doubt (which for many artists, creeps out of them like a shadow against a wall).

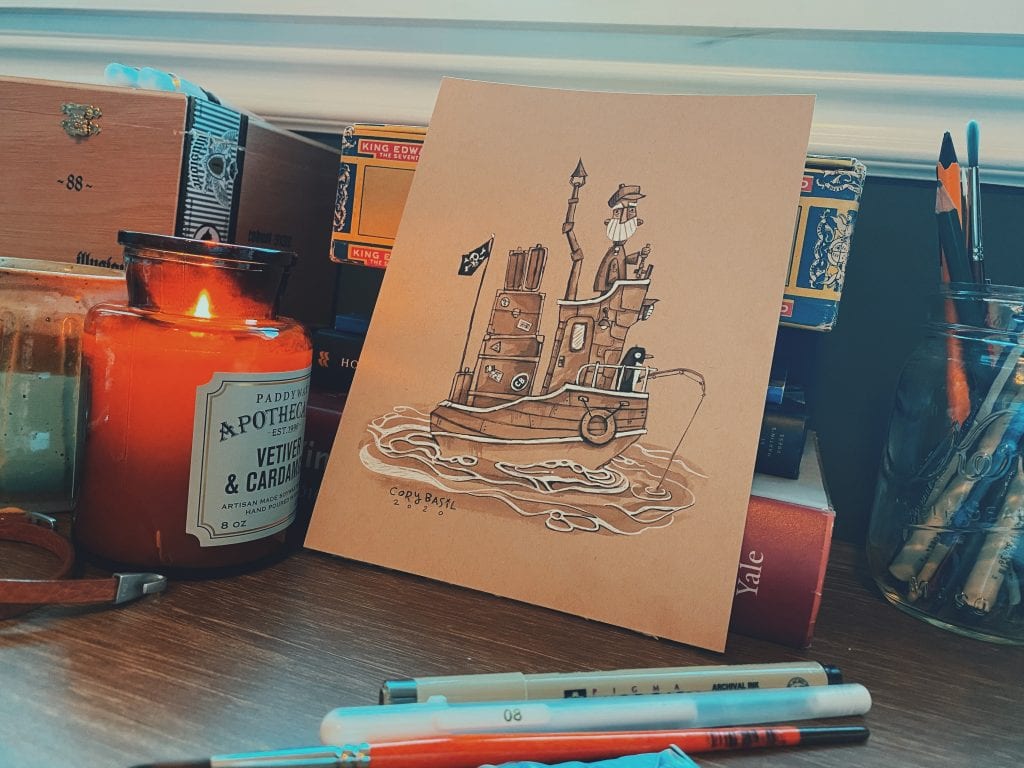

The “I must get this done at all costs” work ethic is how he wrote his young adult fiction novel, The Perils of Fishboy: A Tale Split in Two. Cory’s goal with the book is to produce heavier, emotionally-intelligent content for younger readers and provide them with literary adventures where they can be treated just like grown-ups. “If I live a long life, and have time, it will be a five-book series with a singular arc,” he says, “With many compelling stories in between.”

His recent signing with talent agency William Morris Endeavor shows that there’s an interest in stories like ‘Fishboy.’ Cory tells Launch Engine that the second book is written and currently looking for a home. Cory shares that he misses the characters from ‘Fishboy,’ and he’s looking to return to them soon. With the COVID-19 pandemic affecting the publishing world, plans to have a book formally published are on hold. And since his bills aren’t going to pay themselves, Cory has pivoted to other projects, all the while burning the midnight oil churning out new story ideas through writing and illustration.

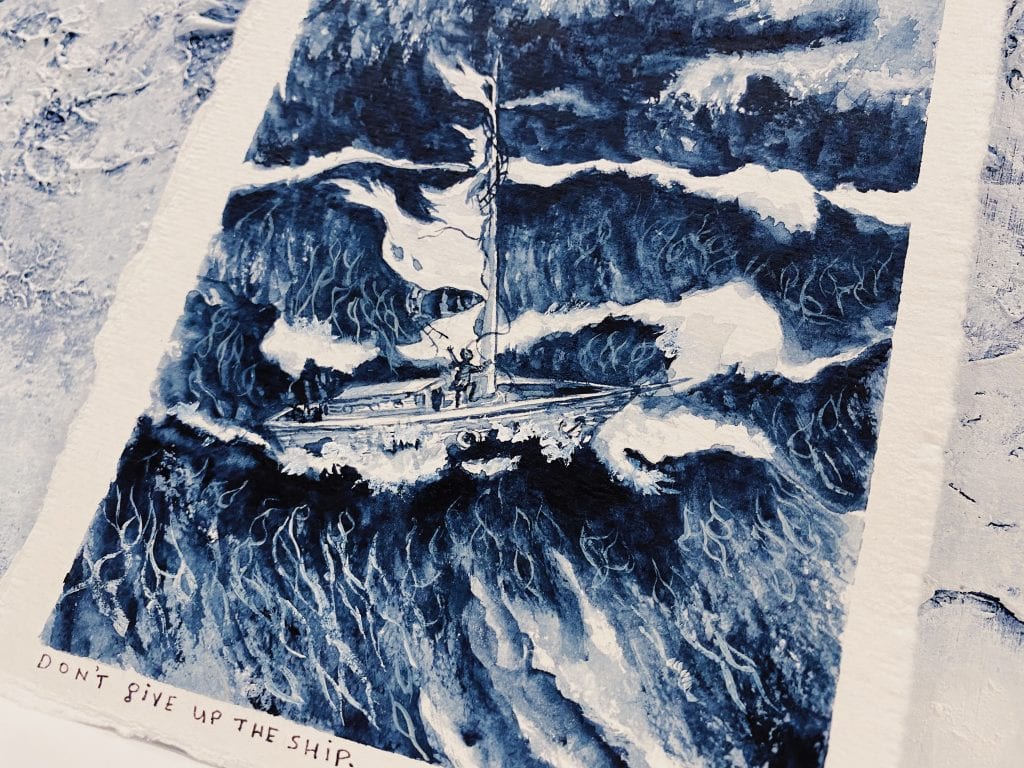

Graphic design work for others fills out an already-hectic schedule of painting, illustrating, and writing. In terms of painting, Cory recently completed his “Corantine Paintings” series, in which he completed 75 paintings in 75 days. Corantine covers a number of subjects, including: dealing with isolation, appreciation for frontline healthcare workers confronting the coronavirus, and kindness to others in a time of emergency.

“I loved the challenge,” he says of the series. “Each piece took between eight to twelve hours a day. Most days, they took ten hours to complete. From conception to rough sketches, to creating the final painting and writing a companion piece… All of that took so much time and zapped me… emotionally and physically. I planned on jumping back into it a couple of weeks later, continuing it once or twice a week, but… months later. I still struggle with the burn-out that ensued.”

Though he still hasn’t found his second wind to replicate the success of Corantine, Cory was able to sell 73 of the 75 pieces he created for the series. In addition, he was gratified to see that it was surprisingly well-received. He says that many people who admired the pieces did so because his work captured what they were feeling during the quarantine. He explains, “I had really great input from people, mostly in private messages.” He adds that his work was appreciated by entire families who would sit down and watch the videos of him creating the pieces together; something they looked forward to each and every evening.

Aside from Corantine, he has other children’s book projects. “I’ve 20 or so different stories that are dancing about in my head at the same time. I’m working them out as fast as I can,” he says.

Of course, Cory is a person living in a particular place and time. He, too, is experiencing the uncertainty and upheaval we all are. How do you balance channeling your creative energy and coping with our trying times? For his part, after moving on from the Corantine Paintings, Cory has been trying to cope by making art that is relevant to younger people. This is his way of trying to avoid the insanity and negativity found all over social media and in headlines everywhere. He realizes all too well that the trap of getting too involved with politics and losing focus on one’s art can be unhealthy. Creators can get distracted and lose productivity, which is something he simply can’t afford to do.

“I’m not a politician, or a pundit,” he says. “If I’ve a part in making the world a better place, it’s going to be through my art. If I communicate with the world in the same way as everyone else I’m just adding to the noise. A noise that has surpassed deafening levels. My value is in my singular voice, and I must find unique ways to use it. The world needs healing, not shouting and separation.”

Knowing that a lot of people are just trying to survive right now, Cory’s concentration has been on trying to make COVID-19 less scary. He’s working on a children’s book from the perspective of a child. He is focusing on how the experience doesn’t have to be troubling. He was inspired to make this book after seeing a stressed family with children, terrified, acting as if “zombies were going to get them.” He says, “There was this one kid in particular, who was just grabbing onto his parents, looking around the airport… eyes peering above an oversized mask. It just made me sad knowing that kids have to deal with this.”

Cory is considering the possibility of publishing his own version of this book and making it available through online outlets. At the time of writing, he’s uncertain about how he will present the project after completion. He remains hopeful and says that it’s important for creators and patrons to stand together, and he feels that both need each other now more than ever.

For further information about Cory Basil’s artwork, including where to buy pieces, be sure to visit his website and social media.