What makes someone an expert? Does it take being in the field for a certain number of years? A particular number of clients? Having someone hail you publicly as “an expert” in the world of business after years of toiling away in your industry?

What if being an expert was as simple as recognizing certain patterns that others don’t see, and then charging people for access to that information?

According to David C. Baker, that’s exactly what an expert does. David is an advisor who has served over 900 firms through his “Total Business Review” process. This top-to-bottom service covers things such as employee retention, new business audit, or even a total business reset.

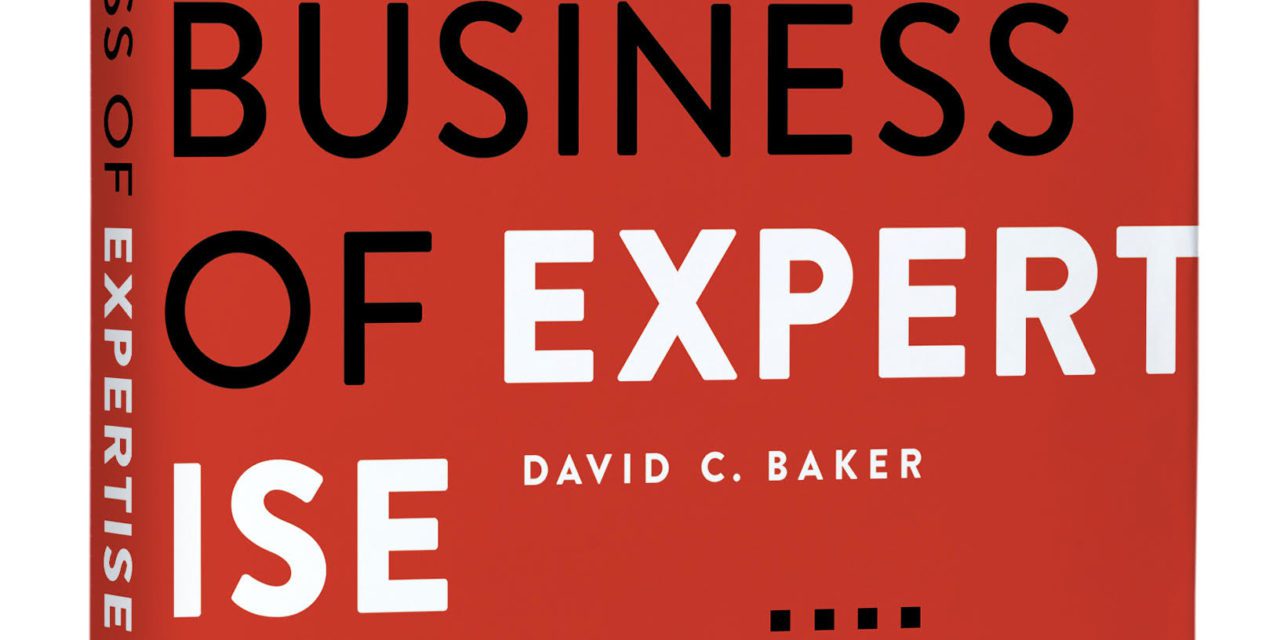

David is also a professional speaker, co-host of the “2Bobs” podcast with Blair Enns, and an author of five books. Of particular relevance to this discussion, it should be noted that one of the books is “The Business of Expertise: How Entrepreneurial Experts Convert Insight to Impact+Wealth.”

David’s sage advice has been recognized throughout the country. According to the 2018 The New York Times article entitled “Fake Experts Abound. Here’s How to Find (and Be) a Real One,” David is the real deal. Carl Richards writes, “What’s so compelling about Mr. Baker is that he’s an expert on being an expert. And because he is so knowledgeable about what true expertise entails, he is able to help both real and fake experts alike. If you’re a fake expert, this book will teach you how to become a real expert (assuming you actually care about that). And if you’re a real expert, this book is a road map to converting your insight into greater impact and financial security.”

How did David become so familiar with the parameters of expertise? The answer to this starts with what caused him to choose his career.

“I’m more of a mutt than anything—in the sense that I didn’t choose a particular path… This world sort of found me,” David tells Launch Engine. The son of two medical missionaries, David was born in Detroit. When he was four, his parents moved to Costa Rica for a year to learn Spanish, and later traveled to Guatemala. There he grew up with a tribe of Mayan Indians in a village far away from everything he had once known.

“We lived with no power, no running water, [and] no roads for 13 years,” David remembers. Eventually, he returned to the U.S. in high school. Inspired by his parents’ desire to share information freely and help other people, David wanted to teach at the graduate level.

David says, “It wasn’t meant to be, for a lot of reasons. So, I thought, ‘How hard could it be to run a marketing firm? The marketing stuff I see, I’m not impressed with it. How hard could this be?’ Turns out, it was a lot harder than I thought.”

Undeterred by the challenge, David buckled down, and started his firm in 1988. David liked the general space of marketing, but didn’t care for having to run his own firm.

He didn’t realize it at the time, but David was resisting his true calling. In 1993, David was approached by a friend who ran a subscription-based newsletter. His friend asked him to write an article on the financial management of his firm. David agreed, and produced an article that got a lot of positive feedback. Later, David spoke to his friend, pitching to him that he should use his huge following to offer consulting services to the newsletter subscribers. His friend sensed that this was a good idea, but that it would be better suited if David did the consulting instead.

David recalls, “And then, you know, without any pause, he said, ‘I’ll put an ad in the publication, and you just give me 10 percent of everything you make….’ I didn’t think anything would come of it that, [but] people started to call really quickly.”

Piggybacking off of his friend’s notoriety, David launched his career as a marketing consultant. Nine months into the work, David had found a new direction helping other marketing firms. Thus, in 1994, David transitioned from being a marketer into being an advisor. He explains that he didn’t help the marketing companies with the external work that was seen by clients. His area of focus was internal to the firms. This included things like assessment of day-to-day operations, helping them position themselves in the marketplace so that they could make more money, what to charge clients so that they’re not underbilling them, and even tweaking their company culture.

“I didn’t help them with the marketing thing because it turns out the world doesn’t need another marketer,” he laughs, stressing that the world needs better marketers. “I wanted to help them make their businesses successful.”

David’s outlook on marketing is that it’s a largely unregulated field because many people aren’t sure that company marketing effects will make a difference for the client. Unlike massage therapy, there aren’t necessary certifications or barriers for entry into the world of marketing.

David says, “[Marketing and public relations] are dirty words, and they’re also like rain dancing. ‘I don’t understand it. It looks weird but I kinda need it.’” He adds that because people don’t see an immediate ROI with marketing efforts, many clients may be quick to dismiss a marketer’s hard work.

But the problems aren’t all on the client’s end, and David explains that there’s a lot of room to improve marketing.

“Their standard is much lower than the practitioner who sees all this beautiful detail that other people don’t see,” David says. “And so the practitioner is ignoring the project management, the account management—all that stuff in the strategy—doing what they love. And the client is… sort of a victim. Like, ‘I’m glad you’re here, you’re paying the bill, but let me get back to the work.’ Whereas the client knows this is a real business need. So, yeah, there was a lot of room to improve the practice side of it, too.”

The wisdom that David offers his advisory clients is timeless. David says, “In terms of the stuff that I do a lot of, it hasn’t changed over the decades. It’s usually focused around how to position their firm. And the odd thing there is—that’s what they do for a living, but they can’t do it for themselves. They’re inside the jar, and they can’t read that label….”

With all of the tech in the world today, age-old problems like managing growth without cratering and handling a company merger are still problems David’s clients have to address.

One of these problems is the dreaded issue of “How much should I bill my clients?” David himself wondered this over the years, as one of his core programs started at $4K before it graduated to a $20K service.

David says this all traces back to confidence in supply and demand—and recognizing the similarities or differences between one’s clients. Until an entrepreneur learns to do this, they’re “just drinking from a hose every day” because the client will always feel brand new.

“There’s no point in not raising your prices if you have plenty of work,” he states. “But… it’s not that as much as just getting smarter. I mean, in the early days, I was learning mainly from my own mistakes, the mistakes I ran, and running the kind of firm that these new clients of mine were running… But very quickly—I would say within a year and a half or two years—I began to learn from the pattern, matching opportunities of going one firm this week, another one this week. It’s like, ‘Oh, it’s just like a laboratory!’ Then, every six months. I’d sit back, and I’d have this stack of manila folders back then before Dropbox… And I would say, ‘All right, two piles here: firms that are really, exceptionally good and the firms that are really exceptionally average. Well, what are the common things here? What is it about what the principal did? About their background? About how much they charge? About the service offering? About the purchase paths? And then you start to say, ‘Oh, my goodness! That’s amazing!! Now, I need to tell other people about how they could be in this pile.’”

David admits that making smarter moves helps entrepreneurs in the long term, but at the sacrifice of short-term prospects. “You have to be comfortable with leaving a lot of unmet needs around you if you’re willing to climb a particular ladder,” he says. It may go against one’s feelings, but not bending to pick up every piece of low-hanging fruit keeps people focused on looking up.

David adds, “That’s one of the reasons why people who are really good at what they do in their field charge more—because everything that they’ve done up until that point enables them to do more efficient and more effective work. Like, ‘Yeah, it took me 30 minutes instead of four hours, but it took me 20 years to get to the point where I could do it in 30 minutes.’”

David is currently writing his sixth book.

For further information about David C. Baker, be sure to visit his website and social media.