How should “addiction” be defined and treated? For communities trying to solve substance abuse problems, this is a pressing question. Should it be viewed as a harmful, selfish behavior that should be punished? Or is it something that should be regarded as a disease that requires compassion for the sufferer and medical treatment so as to help the patient recover their health?

North Carolina startup OpiAID opts to take the second, more humanistic path. OpiAID believes that “Addiction is a physiologic response, not a moral failing.” They treat addiction as one would treat a disease. In so doing, the data science company offers software solutions to monitor the health of those in Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) rehab centers.

OpiAID’s website details why such a company should exist, stating, “From 1999 to 2017, more than 700,000 people have died from drug overdoses. It is the leading cause of death in the United States for those under the age of 50. It is estimated that 68 [percent] of the more than 70,200 drug overdose deaths in 2017 involved an opioid. On average, 198 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose. The total cost to the US economy is over half a billion dollars each year due to this epidemic.”

Drug addiction is a disease that occurs throughout the population, cuting through ethnic and socio-economic boundaries. In response to this communitywide threat, Founder and CEO David Reeser started OpiAID. It was his conviction that OpiAID could help to correct problems persisting in his home town of Wilmington, North Carolina.

“I saw a need in my community,” David explains to Launch Engine. “I initially started this company back in 2018, and I did it because I looked in my backyard, this city Wilmington that I called my home. …And I got hit with this statistic that 11.6 percent of our working population is addicted to an opioid—in Wilmington! Which basically means that my neighbors in my backyard are waking up every day in withdrawal, and they need to take something just to be able to function.”

David says that many people who are abusing substances don’t continue taking them out of desire. They continue taking them because they can’t stop themselves. David explains that withdrawal symptoms include feeling like one has the flu.

David admits that he struggled to process the alarming statistics that outlined the sheer magnitude of the problem in his community. . “How could that be true?” he recalls asking himself as he attempted to reconcile the ugliness of the community’s substance abuse problem with what he had known as a safe and healthy neighborhood. After doing his own research into opioid addiction, David wondered if there was something that he could do to solve the problem. His solution? OpiAid.

So what IS OpiAID?

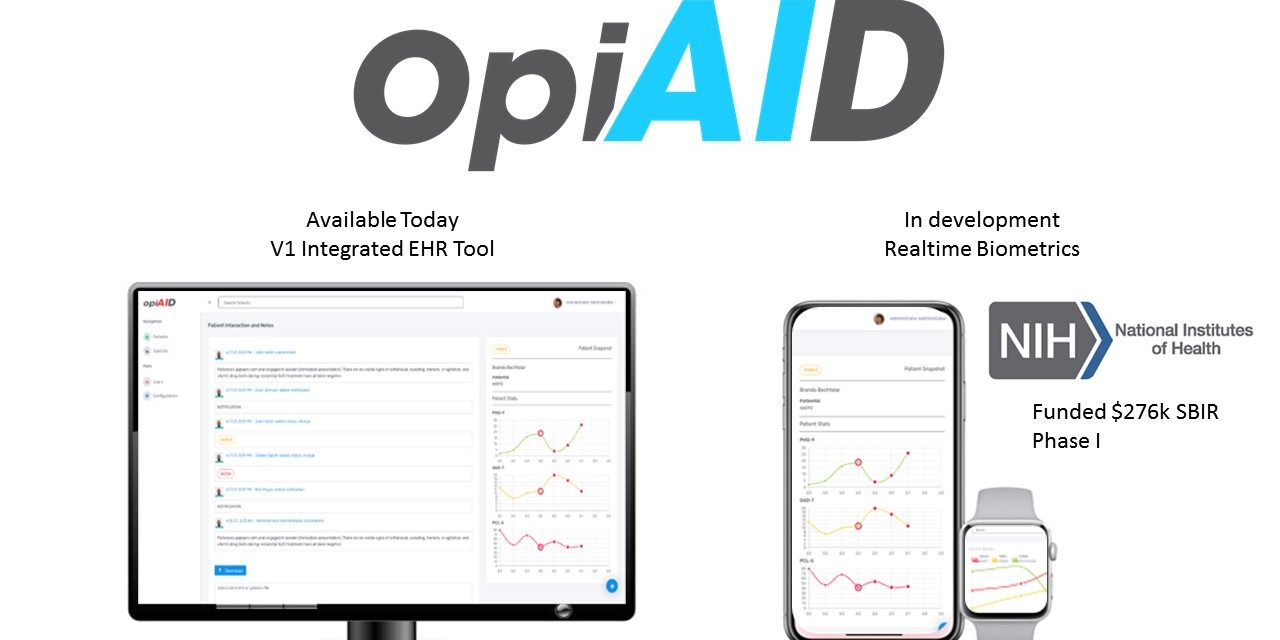

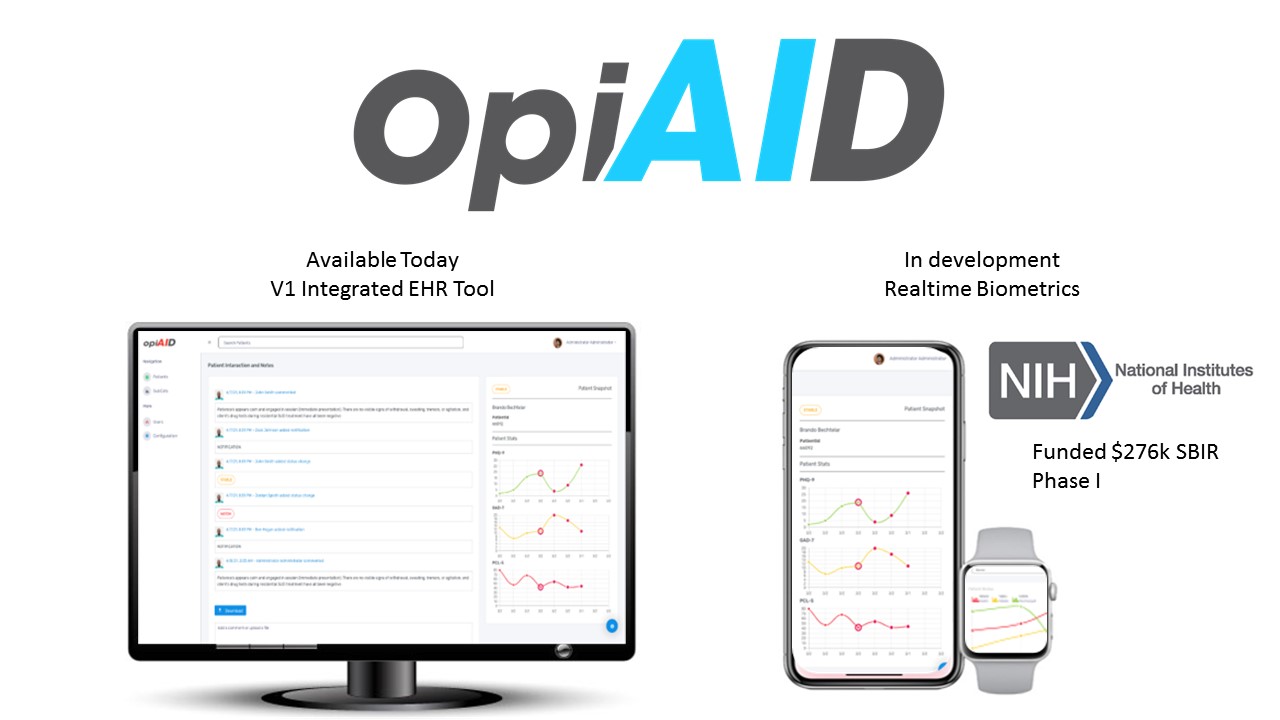

According to David, one may think of OpiAID as a voluntarily-enabled software for the treatment of substance use disorder. “Our tool integrates into the EHR [electronic health record] of the provider… So those who provide medically-assisted treatment, our software bolts onto their EHR and accesses—almost like a Google analytics, if you will—extracting data and taking that data out of the EHR and creating an interpreted data that plots the scores and metrics over time. So it basically pulls out the things that we know that are important—like clinical assessments and biometric data—other data points and plots it over time.”

This biometric could measure a number of markers, such as heart rate or breathing, which are common features for many smart devices currently on the market. Giving rehab centers this information to chart, employees who oversee a patient’s wellbeing can predict who is likely to experience a relapse in their battle with addiction, which David says is the point of the software. Per David, Only 1 out of 3 people in drug treatment centers complete the program.

OpiAID’s “asks for data” shouldn’t be seen as intrusive. Its software instead provides a greater amount of data—as well as comprehension—of information that may be already available in rehabilitation settings. Gathering this data, OpiAID uses machine learning to outline a course of where one might be headed.

David says that at this time OpiAID has no physical hardware, and is not a medical device company. However, the company is currently doing research with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to figure out how wearable tech could automatically upload the data into OpiAID’s system. This was made possible through a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Phase I Award for $276,000 acquired through the NIH’s National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Small Business Programs, which fund businesses that innovate drug abuse treatment. This research is being done with Wilmington drug rehab facility Coastal Horizons Center.

According to David, the completion of this research will make OpiAID the first company in the nation to have a digital platform for the treatment of substance abuse disorders that’s actually looking at biometric data. Being the first company to gather biometric data in such a way, OpiAID has earned partnerships from the likes of Meharry Medical College and the Network for Entrepreneurs in Wilmington (NEW). This technology is estimated to be available by 2023.

Simply stated, the ability to gather biometric data in the fight against addiction is a gamer-changer. It allows those who are treating those suffering from addiction to see trouble brewing before it comes to a head. David explains, “It’s almost like witnessing an earthquake. You know, there are pre tremors that happen before the earthquake happens… We are seeing that already in the data. Before anyone’s actually noticing that they’re going through withdrawal… the body’s already sending signals that something is happening. So, we’re going to be able to see it before the event.”

Add a connecting paragraph that notes how there is a personal dimension to this technological development.

David reveals that there was also a personal element that compelled him to help others fighting the addiction beast. He says, “You know, in my family, my older sister had some struggles with substance use. And I looked at it at the time like, ‘What, you just got mixed up in the wrong crowd?’ She was older than me. And my father—while he wasn’t addicted to opiates—he was addicted to cigarettes, and it [that addiction] took his life. My father passed away when I was 16 of lung cancer.” What’s more, David’s mother became an alcoholic after his father’s death, and had a “lost decade” of her life due to drinking.

All this painful family history clearly set the stage for the creation of OpiAID. David is well aware of this. He says, “There are no coincidences in life.” His own familiarity with the carnage brought about by addition plays an essential role in his efforts to help others get healthy. He explains, “All my pain, all my heart, all my ideas, everything that I have, I pour into trying to help somebody else. I walked through this so that I could have the perspective and the strength to be able to do something about it… And that’s really what drives me.”

For further information about OpiAID, be sure to visit their website and social media.