Ice cream is a very old dessert that has a lot of history. According to the BBC, “An ice-cream-like food was first eaten in China in AD 618-97. King Tang of Shang, had 94 ice men who helped to make a dish of buffalo milk, flour and camphor.” Going back even further, the site also states, “A kind of ice-cream was invented in China about 200 BC when a milk and rice mixture was frozen by packing it into snow.”

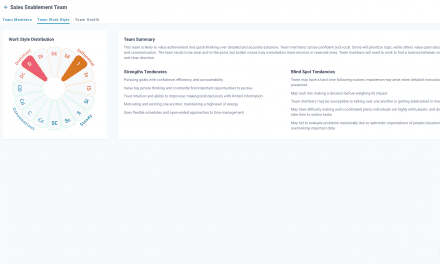

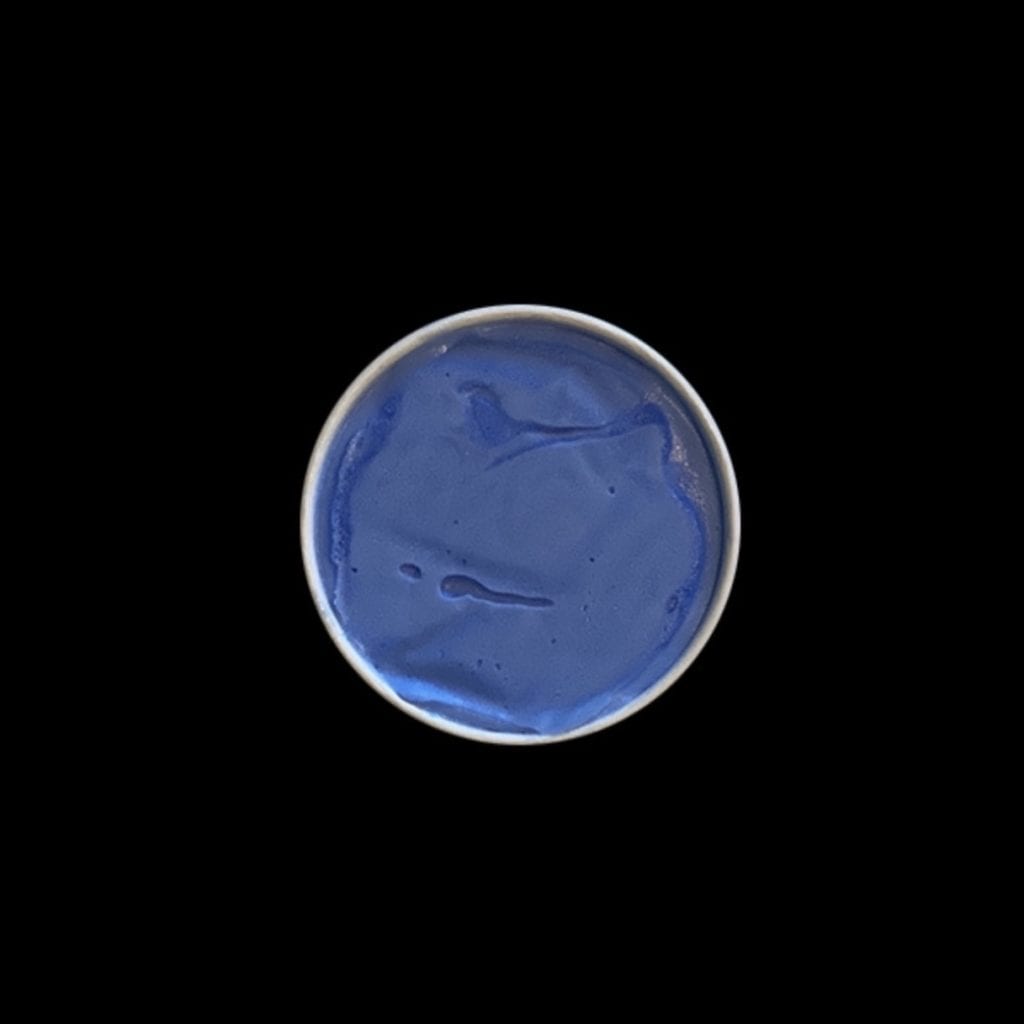

Founder and owner of SATURATED Ice Cream (SATURATED) Lokelani Alabanza loves the history of food. Lokelani studies it so that she can make throwback flavors as well as what might be considered new classic fusion flavors. The SATURATED site describes its wares as “plant-powered, hemp-derived CBD ice cream,” listing flavors such as Peppermint and Oreo, Sunflower Butter Stracciatella, and Le Mango as available for purchase. Lokelani explains that some ice creams are offered seasonally, while others are available year-round.

Currently operating without a brick-and-mortar retail location, Lokelani tells Launch Engine that because she sells CBD (cannabidiol) products online, many website building platforms wouldn’t host her web store. “We hit a lot of speed bumps,” she admits. “But now, it’s like it finally happened.” She describes being in the digital marketplace for CBD products as, “an odd, gray area.” She asserts that those looking to get into this particular marketplace should find a mentor already in the area.

Regarding the SATURATED products containing CBD, Lokelani explains that there are three types of CBD: “full spectrum,” (which isn’t legal in the State of Tennessee because it contains THC), “broad spectrum,” (which contains multiple chemical components of the cannabis plant, but not THC) and “isolate” (which is pure CBD).

She says, “Mine has isolate powder, which is 99.9 percent pure CBD. So it’s stripped of the waxes, the terpenes, the fibers. It is just pure CBD… You don’t get a high.”

Just like the dessert she’s come to love, Lokelani was also shaped by geography. From California’s Bay Area, her family moved to southern Oregon when she was still in high school. After graduating, she and some friends visited Europe. Because her grandmother was Danish, Lokelani was curious about getting in touch with her roots in Denmark. She lived in Svendborg, Denmark, for a few months, learning from chefs.

“And I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, I think I want to cook,’” she recalls. Once she returned home, Lokelani shared her new passion with her family. Then, after taking a job at a restaurant, a chef advised her to attend the prestigious New England Culinary Institute. At the time, Lokelani was less interested in desserts, and wanted to make appetizers and entrees.

Lokelani graduated from the New England Culinary Institute, later moving to Los Angeles. After a difficult time finding work, Lokelani was hired to be a pastry assistant at Grace, a now-shuttered dining concept owned by husband and wife restaurateurs Neal and Amy Knoll Fraser.

“[That work experience] would ultimately change my life, because that would be the beginning of my career,” Lokelani says. She refers to the experience as one that laid the foundation for her to learn food. It was during this period where she was fortunate to have noted culinary figure Elizabeth Belkind serve as her mentor to “teach her all things pastry.”

Following her time working under Belkind, Lokelani later got work at two other restaurants that gave her the experience she needed to master pastries. In 2008, she got married and moved to Japan, where she lived in Okinawa for four years as a private chef. Okinawa’s food culture is very much colored by its traditions, with consumers and restaurateurs placing value on the ceremony and proper customs created by their ancestors. She describes it as “exquisite,” and “very old, very methodical, very specific.”

“Everything has detail…” she says. “Even when you go to the store, you’re looking at products and you go, ‘Ugh. Why didn’t we think of that as an American?’”

In 2012, Lokelani and her family relocated to Las Vegas. In spite of having a strong resume, she had trouble getting work for a period when she was there. She started her own business making hand pies, or small, fully-cooked pastries filled with fruit. While looking for work, Lokelani was offered a job at Thomas Keller’s Bouchon Bakery, where she earned her blue apron.

After working at Bouchon Bakery for a year, Lokelani moved to Nashville, and wound up taking a job as an executive pastry chef for the Hutton Hotel in 2017. It was here, while doing an event for the James Beard Foundation, that she decided to make 250 ice cream bars.

“I wasn’t interested in [ice cream]. I was a pastry chef… I composed dishes. I was very good at it,” she explains. Lokelani wound up leaving the Hutton Hotel after a large personnel change. A friend offered her work at Homestead Manor, a 45-acre historical farm that was an event venue space in Thompson Station at the time. Owned then by A. Marshall Hospitality, Homestead Manor brought Lokelani on as a pastry chef, and then later, as the culinary director for Hattie Jane’s Creamery.

“I always say, ‘Ice cream found me,’” Lokelani jokes. “It was like I walked around a corner, and there it was. ‘Oh hey!’”

Lokelani had always used ice cream with her food, but it was more of just a supporting actor, rather than the leading man for the desserts she made. Working in a creamery, Lokelani was now in the uncharted territory of making the ice cream from scratch. Working with commercial equipment and the standards expected of professionally-made ice cream gave her this massive platform. She describes the ice cream makers “guild” as “a secret club that’s very hard to get into, but once you’re in, you’re in.” Many members of the “secret club” don’t want to give newcomers information. As a result, there’s a lot of trial and error around ice cream scoops, containers to be used for ice cream, and what ingredients will or won’t work with a batch of ice cream.

Lokelani shares that “the dairy business is huge here” in Tennessee, and that consumers in the state are loyal to brands they feel have done well by them. For a long time, Lokelani wanted a product that she could consider her own. She originally thought that that would be pastries. But after considering all of the untapped potential of ice cream in the State of Tennessee, Lokelani switched gears.

She explains, “When I figured out where my culinary stance was right, I knew I wouldn’t own a restaurant… I knew I wanted product. I was like, ‘How can we make… good, quality product?’ And so, when I started making ice cream, I realized, ‘Oh my gosh! This is product! Like—I’m making product that I love!’”

To her, the most potent ingredient in ice cream is nostalgia. A story or an old recipe will evoke a memory for someone eating the ice cream. That person will then share with Lokelani that the ice cream she makes reminds them of a loved one. From such feedback, Lokelani has concluded that serving ice cream isn’t merely serving a treat. It’s participating in a living piece of food history. Lokelani collects old cookbooks to study the recipes of previous generations.

As a Black culinary professional in the South, she tells Launch Engine that so much of the history of Black food has been lost to popular culture, including the history of ice cream. So, she has made it her mission to carve out Black culture in food through recreations of old recipes, as well as making new recipes. Lokelani has created over 350 flavors of ice cream, which she has broken down into historic, contemporary, and experimental flavors.

But what got Lokelani interested in plant-based ice cream made with CBD? She answers that by saying she felt that everyone deserved to have good ice cream, even if they couldn’t handle dairy. While she was working at Hattie Jane’s, she had a friend who was terminally ill. During their last visit, Lokelani’s friend told her that CBD had done wonderful things for her.

“I started to think about… what would be the thing that you would have in the last moments of your life?” she says. Ice cream itself could bring joy to people, but Lokelani knew that ice cream plus CBD could literally ease the pain of many as “a small, good thing.”

In March 2020, after COVID-19 first hit the Volunteer State, Lokelani was laid off from her job at Hattie Jane’s. The idea for SATURATED had been percolating in her head for some time, however. Rather than try to work for someone else, Lokelani brought her business to life. First perfecting small batches at her house, she was able to move to a professional kitchen her friend had built and offered to her.

Now with access to the equipment she needs to make larger volume batches, Lokelani has been able to build SATURATED’s following during the pandemic. She says that the response to the various flavors has been great, with last year working as a product-market test phase. Pop-up events and partnerships with local vendors have helped get her brand in front of Nashville consumers—including City House with an opportunity to make ice cream cookies.

Running the business as both founder and employee during a pandemic has been a wild ride for Lokelani, who went from being laid off to making her own signature desserts. Having weathered the pandemic storm and come out stronger for her efforts, Lokelani wants to expand her co-packing and distribution plans for 2021. Once she’s got that figured out, she’ll be able to concentrate on tinkering with new ice cream ideas in the kitchen and reaching a wider audience.

“The next goal is really to get it to see how far we can get Saturated to travel outside of Nashville,” she says.

For further information about Saturated Ice Cream, be sure to visit its website and social media.