Art is a tool for reflecting on the human condition. The emotions, the ideology, or even the hidden details of a people’s history may be presented for consideration in an artist’s search for truth or meaning.

Through her artwork, Sisavanh Phouthavong Houghton has selected portions of her Laotian heritage to exhibit in venues across the country, including the Minnesota Museum of American Art, Asian Arts Initiative, Hunter Museum of American Art, Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, Huntsville Museum of Art, and The Reece Museum, with permanent collections on display at Hunter Museum of American Art, American Embassy, Paramaribo, Suriname; Legacies of War Office, Washington, D.C.; Tennessee State Museum; and Pinnacle Bank Headquarter, Nashville. Sisavanh is a visual artist and art professor who teaches advanced painting at Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU). She considers herself a multidisciplinarian who “doesn’t sit still well.” On top of various methods of painting, she works in many mediums, including bronze, aluminum, wood, collage, and fabric.

“I started making art as a form of therapy. I think a lot of people are that way as well at a younger age, where you’re allowed for some naiveté. And just creating, right? There’s no rules, no regulation,” Sisavanh says.

Initially from Winfield, Kansas, Sisavanh was born into a family that relocated from Laos to escape the Vietnam War. As a child whose family escaped war and was just trying to survive, she knew that she wanted to be an artist. She was inspired by the natural draftsmanship of her two older brothers, and spent many hours drawing. Sisavanh not only wanted to make art, but she desired to teach art to others. Sisavanh didn’t decide to pursue her true calling until her time as an undergraduate at The University of Kansas, switching her studies from biochemistry to graphic design, illustration and finally majoring in painting. At this point, neither her family nor the financial stability promised by other jobs could tempt her from her true calling as an artist. But this decision would be tested.

“What I’ve learned from life is that you take what gets thrown at you, and you ‘make lemonade,’ whether it’s with sugar or vodka,” Sisavanh jokes.

After getting her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree, she married another artist, sculptor Jarrod Houghton. Though they longed to live in areas more suitable for artists, they relocated to Carbondale, Illinois, to get their graduate degrees at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. The selection of this particular academic institution was influenced by both Sisavanh and her husband worrying about their parents getting older. Things gradually got grim, as Sisavanh’s father was diagnosed with cancer. Adding to her stress was the difficulty in finding steady work—although she was able to get a job as a substitute teacher.

As painful as this time might have been for her, life didn’t slow down for Sisavanh. She had her first child in the second year of graduate school. She made the best of her situation, finding a group of artists whom she could love as a creative family. Embracing her struggles as their own, those friends provided child care for her first daughter so that she could take time to create.

Sisavanh expresses, “That’s the point where I felt, ‘Oh, I might be able to do this!’” Through determination and tenacity, Sisavanh was able to survive graduate school. With her degree in hand, she began to look for sustainable work. Her luck eventually changed for the better, when she accepted her position at MTSU in 2003.

In 2016, Sisavanh attended the Lao Writers Summit in San Diego as part of her participation in a group art show. There, she met the Founder of the Legacies of War organization Channapha Khamvongsa. Khamvongsa spoke at the summit to discuss “The Secret War on Laos.” The organization’s website defines this war: “From 1964 to 1973, the U.S. dropped more than two million tons of ordnance on Laos during 580,000 bombing missions—equal to a planeload of bombs every 8 minutes, 24-hours a day, for 9 years – making Laos the most heavily bombed country per capita in history. The bombings were part of the U.S. Secret War in Laos to support the Royal Lao Government against the Pathet Lao and to interdict traffic along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.”

Later getting to meet Khamvongsa the Secret War on Laos, Sisavanh tells Launch Engine that she was moved by what she learned. “[Most of] what’s over there still has not been detonated,” she says, sharing that every year, about 80 percent of the casualties from the bombs that detonate are children who think the bombs are toys. Per Sisavanh, the undetonated explosives also prevent two-thirds of Laos from being farmable.

She says there’s a lack of awareness about the unexploded American munitions in Laos, including the unsavory detail that the 80 million still active bombs left in Laos could cover “most of Tennessee.”

“Even for me, my parents didn’t talk about it. I didn’t know too much about it all. My husband’s a history buff. He loves anything that deals with the military,” she says. Sisavanh had heard about the Secret War on Laos off and on, but it was never something that she gave serious attention to growing up. This is because of the fact that her father was a doctor who served the Red Cross, and he saw the horrors of combat firsthand. Like many who have seen war up close, her father chose to remain silent in an attempt to move on from those painful life experiences. Sadly, history can not and will not be ignored for long. Eventually, the next generation comes knocking, seeking answers.

“The question, I think, for me when I would start making these works… was ‘Why should I care?’ I live in America. I’m not in Laos anymore. How am I connected with it? How do I start speaking about that?’ And what I realized was… I will always have a connection with Laos. It was the purpose, it was the reason—whether you call it persecution or whatever you want to call it—it was the reason for my family to leave.”

Before this point, Sisavanh didn’t think her life had been easy. But the information she learned from the Summit evoked a flurry of memories—like living for two years in the refugee camps in Nong Khai, Thailand. Individual memories—such as screaming hysterically as a child when refugee camp guards almost killed her father—never really registered as far as their bigger social significance for Sisavanh. For all intents and purposes, it seemed that her personal story was missing the first few chapters. But now, after all this time, she was finally able to piece the narrative together.

Learning that The Secret War on Laos played a huge role in her life, Sisavanh used its effect on her as a launchpad for her art. Her works grew beyond her personal inquiries to cover the issues related to identity, displacement, and readjustments to a new society mutually experienced by Southeast Asian immigrants. Some of this has been accomplished through abstract art, as certain issues might be more approachable depicted in a non-literal interpretation.

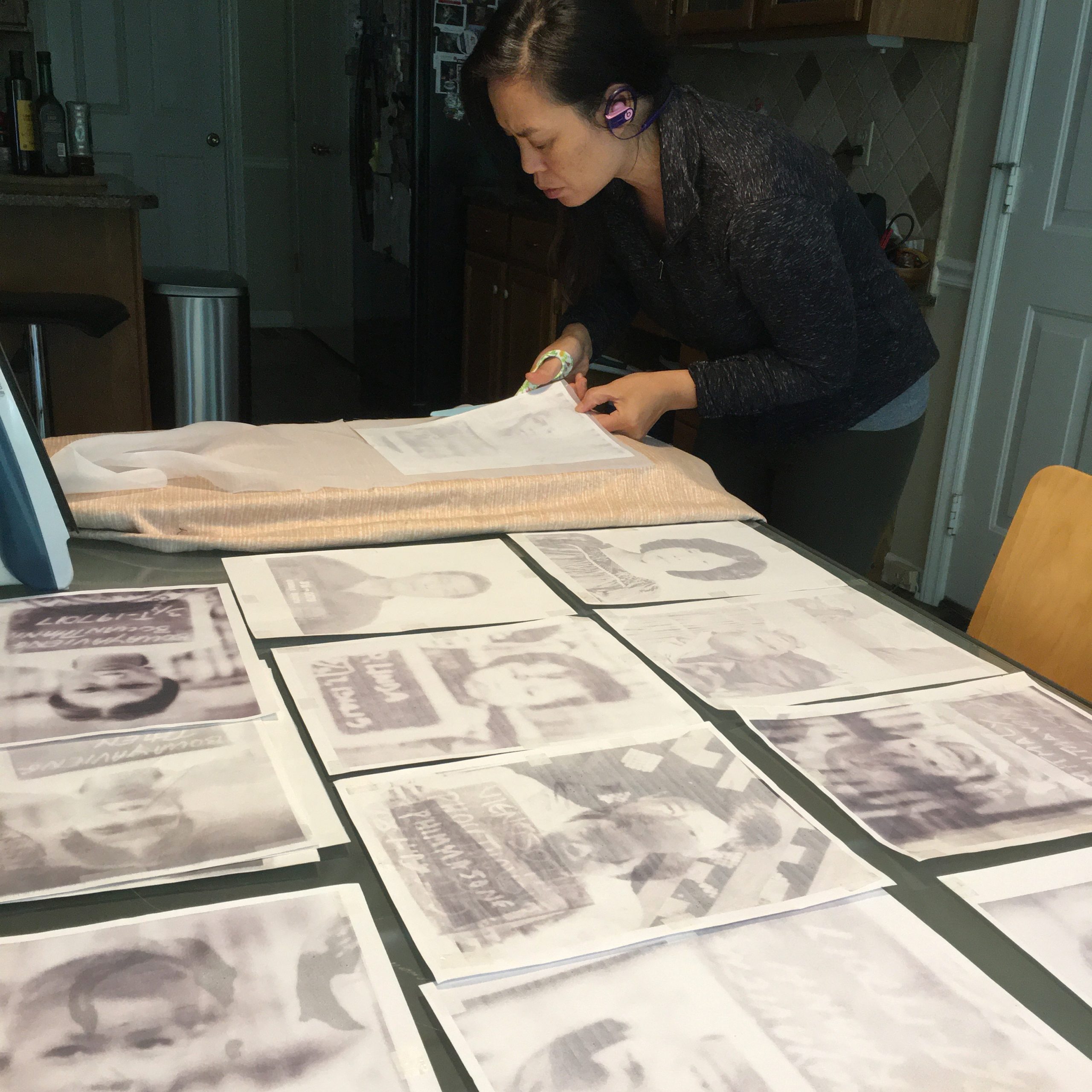

Much of her art begins with research and the collection of visual references. This includes an ever-expanding collection of images relevant to Southeast Asian immigrants, including pictures from the Vietnam War or photos Sisavanh shot in Laos or Thailand. These images could be used as inspiration, modeling, or fodder for collage projects.

One project questions the decisions made by people trying to assimilate to American culture. Entitled “Displacement Series: American Citizenships,” the collection of 11, 2 feet by 3 feet, acrylic on canvas works drew influence from pop artist Roy Lichtenstein. Having to deal with this experience herself when she took the last name “Houghton,” Sisavanh painted Southeast Asian immigrants who changed their first name on their citizenship documents but retained their Laotian last name. She reimagined the subjects as vivid and commercialized comic book art made of Ben-Day dots, which is a uniquely American aesthetic.

“The dots for me were about taking away the individuality of the person and becoming more of just these pixels,” Sisavanh explains. Her process for this series was painting the dots by hand, underscoring the idea that individuals lose much of their character when viewed as part of a group.

In 2021, Sisavanh has already wrapped up three art shows: Group show “The F Word: We Mean Female!” at the Hunter Museum of American Art, “1.5: A Southeast Asian Diaspora Remix” at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, and “Her Liminal Asian-Appalachian Experience” at Slocumb Gallery, ETSU.

Her most recent series, entitled “Transparent Voices,” is a recreation of photos of Southeast Asian immigrants taken before they left refugee camps. The entire project is based on gathered images of herself, family members, and pictures donated by other refugees that show the sadness, fear, anxiety, and hope of dwelling in these refugee camps. The photos used for “Transparent Voices” are printed onto sheer fabric to convey the minimal presence of Southeast Asian immigrants in America. The pictures are connected through symbolic materials like a single gold thread that binds them all, held to the floor with rice bags and adorned with fake marigolds.

“The marigolds play a big part in the [Laotian] ceremonies as well,” Sisavanh explains, noting that the Baci ceremony is an animist ritual to celebrate both life and death. “It has a long history… the smell of it is supposed to ward off evil.”

Pieces from her most recent “Transparent Voices” series will be on display at both the Kansas City Kansas Community College (KCKCC) Gallery, for the “Becoming: Bodies of Trauma, Displacement & Dissent,” art show ending mid-March, and art competition ArtFields in Lake City, SC, between mid-April and May 1, 2021. In addition, Sisavanh and her husband will be exhibiting at the Gadsden Museum of Art for a show that runs between early August 2021, and late September 2021.

Of course, her Laotian heritage is not the only subject of her art. War has been a theme in Sisavanh’s work, with past projects including themes of security in post-9/11 America. Her portfolio shows past works including paintings of birds, colorful reimaginings of landscapes in the rain, and even bronze piece collaborations with her husband that touched on insectophobia.

But her history as a Laotian cannot be denied as an artist, as it is a recurrent theme that funnels personal expression into the experiences of the many who aren’t heard. Just like with the Lao Writers Summit, she wants to provide memorials of a sort to other Southeast Asian immigrants whose cultures couldn’t be packed into suitcases. She’s also preserving these lost experiences to be shared with others, including the descendants of those immigrants who might not get to hear a full retelling of the past.

“It’s about taking history, taking these stories, and making them become part of a culture, part of a conversation that continues,” Sisavanh says. That’s how change is going to happen.”

For further information about Sisavanh Phouthavong Houghton, be sure to visit her website and social media.