Studies show that a parent’s participation in their child’s education enhances the academic success of the child. Parents who are invested in their children’s education should be interested to know what goes on in their classroom. This includes more than just an interest in the teacher’s lesson plan. Of course, we often fail to consider that many stakeholders outside of a given school impact the quality of education in the school’s classrooms in profound ways. One such stakeholder is the Tennessee State Board of Education (SBE).

The SBE oversees educational policies that have an effect on students enrolled in pre-K through 12 public schools. According to the SBE’s website, “The State Board of Education is composed of 11 members representing the diversity of the state — one from each congressional district, plus a student member, and the executive director of the Tennessee Higher Education Commission who serves as non-voting ex officio member. Board members are unpaid Governor’s appointments, confirmed by the legislature and selected based on a passion for service to the people of Tennessee and the education of Tennessee’s children.”

Strategic Communications Consultant for the SBE Elizabeth Tullos engages the public as a public information officer, apprising communities of SBE updates via formal press releases, social media, the SBE website, and other platforms. She works with state education leaders to communicate policy changes and updates to stakeholders, such as legislators, school boards, superintendents, educators, and parents, serving the SBE under Executive Director of the Board Dr. Sara Heyburn Morrison.

Elizabeth is a strong proponent of bringing many stakeholders to the table so as to improve education in the state. She uses the metaphorical phrase “marble cake federalism” to explain how a mix of local, state, and federal actions can influence how students in a particular area learn. Marble cake federalism suggests that local, state, and federal governments are not just different spheres of government shaping policy independently, but rather their roles are intertwined, much like a marble cake.

When it comes to education policy, it’s not just one county or city determining what’s best for their students and then executing a plan, but a mixture of local, state, and federal rules, policies, and laws.

Elizabeth explains, “For example, if you look at Shelby County, that county alone has almost a million people in it, right? But then, within that single county, you have Shelby County schools, you have Collierville Schools, Germantown Schools, Arlington Schools, Bartlett City Schools, Millington School District, and Lakeland School System… All of those different school systems all operate within Shelby County.”

Elizabeth tells Launch Engine that they all have their own leaders setting individual policies. As a result, each school system is a little bit different. In addition, charter schools can be thrown into the mix, with their operation both within and outside of the regular school system.

Local administrative personnel like supervisors, superintendents, board members from local-level school districts and members of the Tennessee School Board Association are all part of the decision-making process when it comes to drafting educational policy for the state. Of course, the input from personnel at local and state levels offers different scopes of feedback.

Elizabeth says that her agency expends a lot of effort in communicating with legislators, the Tennessee Department of Education—which is an entirely separate entity from the SBE that serves completely different functions—school districts, educational stakeholders, and the educational strategy team for Governor Bill Lee.

Elizabeth explains the difference between the SBE and the Department of Education, saying, “The Tennessee State Board of Education makes the policy. The Tennessee Department of Education is really more of the implementation body for policy.” As a representative of the SBE, Elizabeth will frequently collaborate with members of the Tennessee Department of Education to discuss policies, and how the two organizations can best serve the schools in the state.

Despite these efforts at communication, Elizabeth admits that developing educational policy isn’t always well understood. She says, “When a parent or educator has a concern about a particular policy, it isn’t always immediately clear where the policy originated. It could come from the federal, state, or local level, or it could even be a law instead of policy.”

A note on policy versus legislation: Policy is given by those organizations that oversee education. While they have the authority to create and implement policy, they do not have the authority to turn policy into legislation. Legislation—defined as “any law passed by lawmaking bodies”—for education is passed in large part by the Tennessee General Assembly.

One such example of this is the General Assembly’s recent creation of the Education Recovery and Innovation Commission through statute. Per the State of Tennessee’s website, “This Commission was formed to examine the short- and long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on education in Tennessee. Members of the Commission will form recommendations for the General Assembly, State Board of Education, Tennessee Department of Education, Tennessee Higher Education Commission, and higher education institutions to close educational gaps arising from school closures and to modernize the state’s educational structure to create more flexibility in the delivery of education to students.”

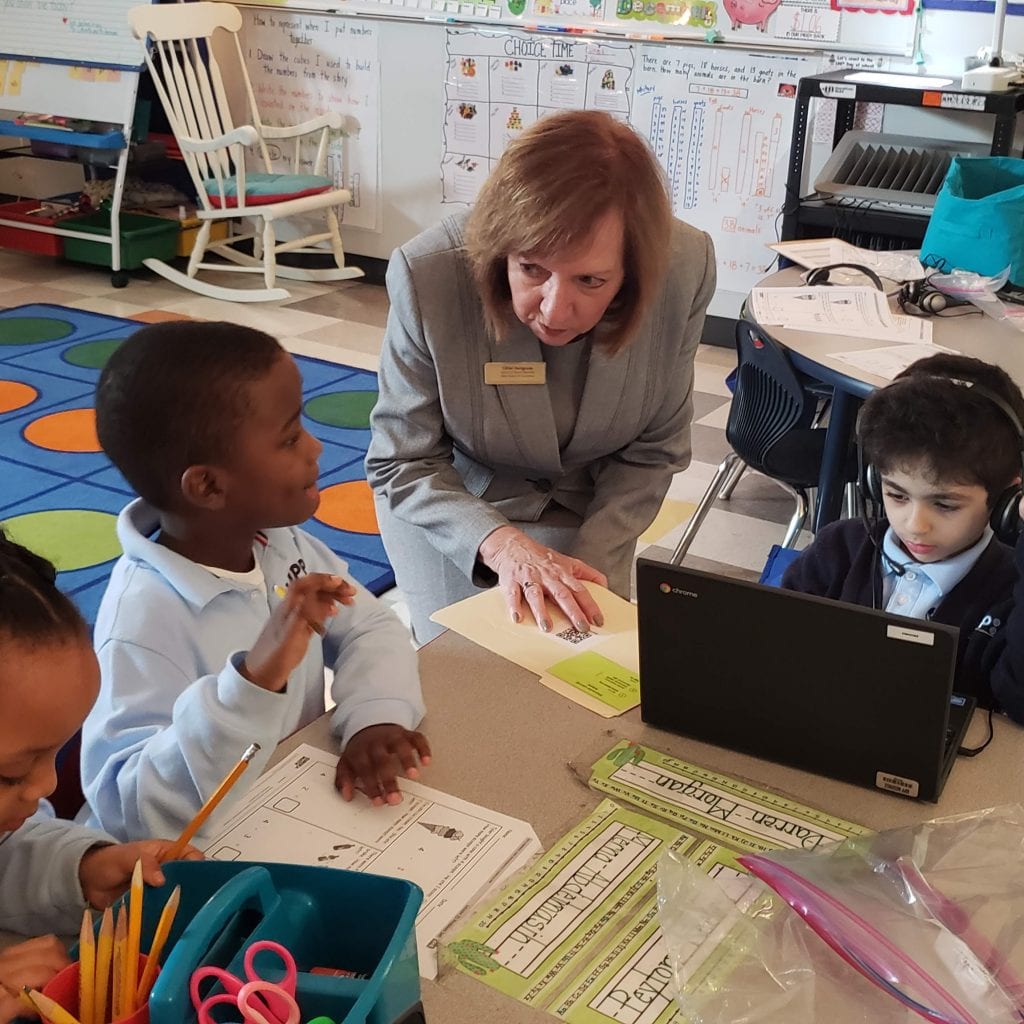

SBE Chair Lillian Hartgrove had previously spoken to the importance of the Education Recovery and Innovation Commission, saying “The creation of this Commission is critically important to all of us in education as we look at the effects of COVID-19 on student outcomes. The State Board of Education looks forward to working with the Commission as it assesses and determines how we can ensure students in Tennessee will not lose ground due to any other health crisis or natural disaster.”

Readers should note that this will not be a simple process. Yet again, its success will hinge on listening carefully to all the stakeholders, a fact of which Elizabeth is well aware. “We’ve been working alongside the Commission to bring in key stakeholders, such as the Tennessee Higher Education Commission, to discuss pressing education issues related to COVID-19,” Elizabeth says, describing the SBE’s involvement in efforts to curb the loss of education projected for students (known as “COVID slide”).

Regarding the implementation of policy, one of the big projects for SBE is the Educator Preparation Report Card, which comes out around February 15 of each year. The project is a tool to help counties hiring teachers, and according to Elizabeth, it’s something only a few states currently offer.

“We collect data on all of the programs that prepare personnel within education, like training programs,” Elizabeth says. “Each year the report card is made as a snapshot of a three year educational cohort. It’s a vital feedback tool that shows educators in the state how many people enroll in or complete educator preparation programs, as well as education endorsements needed for qualifying to teach certain areas, like English as a Second Language programs or special education. A new component has been looking at diversity recruitment and retention efforts.”

Elizabeth states the Educator Preparation Report Card is constantly evolving to meet the needs of different stakeholders in Tennessee. It’s a project that she looks forward to doing every year because it helps prospective teachers connect with available programs.

As part of the SBE’s work in educational policy, the organization is required to review academic standards every six years. At the time of writing, the SBE has just finished the first reading of the state’s math academic standards. This is a yearlong process that requires multiple readings of the academic standards. In addition, two different public surveys are launched to enable the community to provide input on what changes should be made. Educator teams will then sit down and make their own recommendations based on the feedback from the public surveys.

The six year cycle is a standard practice to ensure the quality of educational materials. It syncs up with the state’s textbook adoption cycle, so that the materials selected for classroom use correlate with the agreed-upon academic standards. The selected topics of review rotate every year, with another area of educational focus up for review when the current review is finished.

For parents concerned about what’s taught in their classrooms, Elizabeth advises them to become familiar with their local education leaders, including the district superintendent and elected members of local school boards. She says, “In all honesty, they have the greatest jurisdiction as to what a student is going to experience day-to-day in the classroom, or in the virtual learning space. The state can set the standards, but then the choices about curriculum, that comes at the local level.”

The school board members not only dictate curriculum, they can also set local policies relevant to the schools under that jurisdiction, including items related to when a school should close due to COVID-19 or how extracurricular activities will be carried out during the pandemic. Local school boards also hire the superintendent, who hires principals under them to oversee individual schools and hire teachers and other personnel.

Elizabeth says that by engaging local education leaders, parents and other stakeholders can join the conversations that shape curriculum and local policy.

For further information about the Tennessee State Board of Education, be sure to visit its website and social media.