The medical community’s fight against cancer is one of the longest and deadliest battles the medical profession has ever fought. The National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) shares that “In 2020, roughly 1.8 million people will be diagnosed with cancer in the United States.”

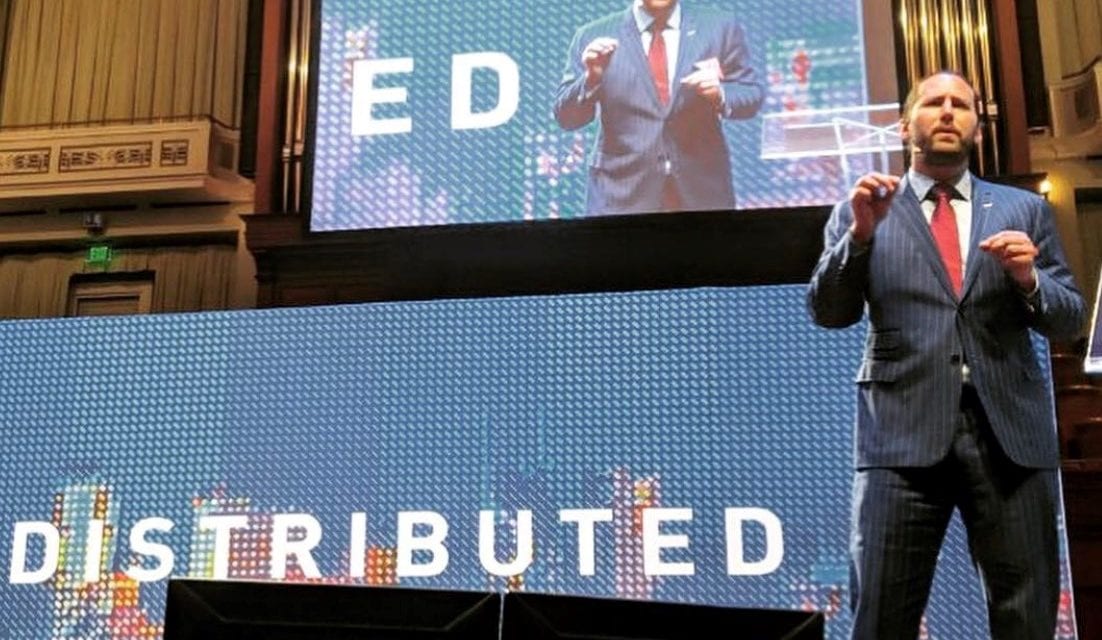

Nashville’s Ed Clay doesn’t mind a fight. In fact, Clay, a former MMA fighter, professional trainer through Nashville Mixed Martial Arts, and previous owner of the world’s largest distributor of Brazilian jiu-jitsu uniforms Gameness made a name for himself by knowing how to take out an opponent. Now, he serves as the President of the United Cancer Centers, Inc. (UCC). From their website, UCC is a “collection of US-based outpatient clinics that seek to redefine the concept of informed decision-making for cancer patients by providing access to a wider array of both FDA-approved and investigational treatment options.”

Ed’s interest in helping people combat cancer and live healthier lives came after his own health troubles. Between 2007 and 2008, Ed tore his LCL, his PCL, and his meniscus while training other fighters. He tells Launch Engine readers, “The team doctor had me on prescription pain pills. And so, I was taking them for a couple of years, and went to stop one day and went through a withdrawal. So, then, over about a six month period, I tried to stop three or four times and wasn’t able to overcome the withdrawal. So, I went to a therapist, and I said, ‘I’m completely functional running my companies, but I would rather have a clear brain and deal with the pain, than a foggy brain and no pain whatsoever.’ The therapist said, ‘America’s behind the times when it comes to opioid withdrawal. Google Ibogaine.’’’

Ed did just that, and found that the psychedelic substance was alleged to stop all opioid withdrawal. Though illegal in the United States, Ibogaine was available in Mexico and other countries. Filled with a mix of skepticism and curiosity, he took a trip to the Mexico City area and took the recommended dosage of Ibogaine. Ed recalls that, after the experience, he never had a craving for opioids or felt any withdrawal symptoms. He explains, “And I was like ‘Well, if this works and it’s not available in the United States, what else is out there?’”

After Ed’s healing and transformative Ibogaine experience, his thoughts went to his mother’s severe form of rheumatoid arthritis. He relates she had gotten multiple staph infections from the medications that she was given (i.e., the standard of care for the treatment of her condition), as well as tuberculosis. To complicate matters, she had also broken her back from a short fall, and her condition made Ed want to retry his luck at finding a treatment not available in the U.S. His search for an alternative treatment led him to a study on Coley’s Toxins for rheumatoid arthritis from the 1920s. There was a hospital in Mexico that had utilized the Coley’s Toxins treatment, but it closed a couple of years before his research. So Ed—along with business partners Scott Nelson and Deddrick Perry—purchased the Centro Hospitalario Internacional Pacifico in Baja California, Mexico to reopen it. Ed made his mother the second patient admitted once it reopened. Ed says that his mother came to the facility in a wheelchair, and three weeks later she was walking.

He says, “To this day, she’s still getting around fine and great. Her RA numbers are pretty much normal.” Ed adds that, while she still faces deformities as a result of the joint damage caused by rheumatoid arthritis, he considers the improvement of her condition and the increase in her mobility a major win. He states emphatically, “Basically, we got her a second life.”

Ed was keeping score for how treatments not available in America had improved both his and his mother’s health. “We were doing alternative things. What was considered alternative,” he explains. “And I wasn’t stuck to any specific side. It’s kind of like, in a UFC fight you can tell what really works and what doesn’t.”

He says that most of the patients that came to his hospital didn’t respond well to the previous standard of care attempts, and didn’t have many other options. “I saw some patients get better, but a lot of patients still died,” Ed shares. “We were looking for other options. And so, my experience with… medicine in general is, you have a couple of different sides. The alternative side is throwing stones at the conventional side. The conventional side is throwing stones at the innovative or alternative.”

Ed’s acquisition of the hospital in Mexico showed that when it comes to serious illnesses, there are serious gaps in the quality of care when people adhere to one school of thinking. “No side has a great answer for stage IV cancer,” he says. “The mortality for stage IV solid tumor cancers… if you go across the board, you’ve got, I don’t know, maybe fifteen percent five-year survival for stage IV? For solid tumor cancers. Leukemia, lymphoma, and testicular cancer, they have good treatments for… solid tumor cancers, not so good.”

Ed began wondering about combining the best treatments for cancer and “how he could build bridges instead of walls.” He started reaching out to members of the scientific community, and coordinated a trial for the drug ValloVax, during which they collected promising data. The trial’s Scientific Advisory Board included former Chief of the Infectious Disease and Immunogenetics Section in the Department of Transfusion Medicine at the Clinical Center of the National Institute of Health in Bethesda Francesco Marincola, M.D.. Ed became friends with Dr. Marincola and another Board member, Vijay Mahant, M.S, Ph.D.; an expert in immune and molecular diagnostics and inventor of a “New Generation” ultra-sensitive test for prostate cancer.

Ed’s friendship with the researchers and personal involvement with healthcare coincided with the U.S. 2018 Right to Try Act. Per the FDA, this piece of legislation “is another way for patients who have been diagnosed with life-threatening diseases or conditions who have tried all approved treatment options and who are unable to participate in a clinical trial to access certain unapproved treatments.” The passage of the Right to Try Act opened more doors for Americans, and as a result, those seeking better treatment may have a better chance of finding it.

“We can do even more in the United States than in Mexico with this legislation combined with compassionate use and other tools,” Ed says. He shares that any drug that has been through a Phase I clinical trial may be given to a patient by the pharmaceutical company making it, if the company wants to offer it. Rather than having to wait until the drug is approved, patients may request access to a drug through their doctor. Ed says that terminally ill patients get access to cutting edge treatments, and that it extends into the Compassionate Use expansion of drug availability by making the access to new pharmaceuticals even faster.

It should be noted that the Centro Hospitalario Internacional Pacifico is a separate facility, not related to the operations of the UCC. But Ed’s discussion of his success with Mexican healthcare or his advocacy for newer drug treatments is a point of contention on which some critics have focused. Statements against Ed’s philosophy on expanded access to treatments might sound something like, “Is it ethical to treat patients with unapproved drugs outside of a clinical trial?” or “Aren’t patients being potentially subjected to drugs that may hurt them further?” Ed appreciates those points, but believes that with genetic testing, medical science is able to better predict which drugs might work better. He expresses that patients facing a terminal illness should have a right to use potentially life-saving treatments, even if they’re not yet approved.

Ed says, “My view on it is that for right to try specifically is that these drugs have been through Phase 1 safety. That doesn’t mean it’s 100 percent safe, but then again no drug is 100 percent safe. But they have been through Phase 1 safety, which is why they put it in the law. And I absolutely believe patients have a right to this. But we are going to be doing much more than right to try. That’s just one aspect. Our team is an all-star team of doctors and scientists that are ready to match medications based on an array of genetic testing. Whether that be right to try, off-label, compassionate use, or a combination of the three.”

That belief is also a core philosophy of UCC, as their website states “the goal of United Cancer Centers is to take a process that typically takes 10 to 15 years with the U.S. FDA and to time collapse this into as little as 18 months. By shortening the gap between scientific discovery and implementation, we can ensure that patients have a feasible and understandable pathway to access the most cutting edge therapeutic interventions. Our hope is that this process can better facilitate the pathway to a cure for cancer through translational medicine.” That “bench-to-bedside” way of treatment is meant to cover as many parts of a person’s health as possible, looking at items such as the immune system and microbiome profile of the patient and a molecular/genetic analysis of the cancer.

From a June 2020 press release, private equity group Vivaris Capital launched its investment product for the UCC. They are currently looking at potential locations for a facility in the Middle Tennessee area.

For Launch Engine readers interested in learning more, Ed Clay hosts both The Big Idea Podcast and The Nashville Current Podcast. For further information about the United Cancer Centers, be sure to visit their website.